It’s Not Enough to Teach Cooking

02 September 2019Workplace settings must be cleansed of chefs with minimal leadership skills, an inability to build teams and those who exhibit erratic behavior.

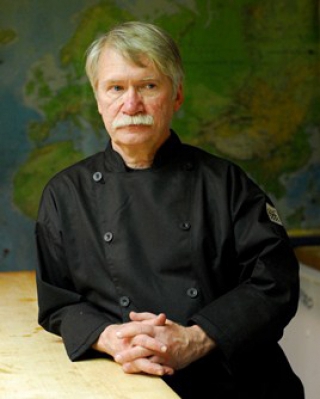

By Paul Sorgule, MS, AAC

Any effective culinary arts curriculum must begin by building the foundations of cooking, skill development, nurturing a student’s palate, and focusing on those entry level aptitudes and standards essential when students walk through the kitchen doors for the first time. In most cases, we culinary instructors and directors do a remarkable job in this regard. So why should we consider changing a proven model? To be honest, I am not sure there needs to be a shift away from this essential focus. But, what I do know is that it is not enough.

As a consultant and restaurant mentor, I find nearly every client with whom I work faces similar challenges – challenges are not addressed adequately anywhere in our system of education. These challenges, from my experience, are much more difficult to address but are likely the most important attributes employers are desperately looking for today.

So, what is missing?

The world of professional cooking is significantly different today than it was just a few short years ago. The need for quality food remains essential, the need for cost controls that lead to profitability are ever-present, and the ability to organize, execute, multi-task and orchestrate is absolutely critical for any chef. What is missing is the ability to effectively, consistently, and appropriately manage people while exhibiting the core traits of leadership in a complex environment with a new breed of culinary employee.

Time and again I receive calls from clients who are frustrated with their chefs and sous chefs. They usually begin by offering glowing accolades regarding their cooking skills and the quality of food they produce. But in almost every case, it is their lack of leadership, their inability to facilitate team building, and their erratic behavior – even hostile interactions with others that drive operators to the brink. At times it almost appears this is a virus present in every chefs’ system. A virus that is out of control and brings even the most talented chefs down time and again.

I have spent endless hours dealing with the effects of this virus and finally decided it was time to dig deeper and seek out the cause. When we deal with effects, constantly putting out the fires caused by hostile actions, then we are destined to find the same scenarios play out over and over. So, here is my assessment and partial solution that involves every culinary program, faculty member, and director.

A baker’s dozen approach

- Understand a chef’s’ personality type

It would be hard to find a quality chef today who does not exhibit the classic signs of a Type A personality. Type A’s are self-driven perfectionists, owners of obsessive patterns of work, totally focused on their job, impatient, easily frustrated, critical of themselves and others, and sometimes easily exhibit erratic and hostile behavior patterns. On the positive side, they tend to accomplish a lot and always strive for self-improvement. While on the negative side, if left unchecked, they can wreak havoc within your workforce leading to a high rate of attrition and damage to their own wellbeing. Now some will say that this is not me, but I am sure we all know plenty of chefs who fit this profile.

Although it is not clear whether this personality trait is somehow genetic, it is likely much of the way a Type A acts is due to the environment in which he or she trained and was mentored. Obsessive chefs help to teach others to be obsessive chefs. To this end, educators can play a role in helping establish better patterns of behavior during the early training stages. Building an aggressive, somewhat demeaning environment because we are trying to toughen students in preparation for the real world or because “that’s the way I was taught” may no longer be an optimum approach. - A need for system-wide standards of excellence

One consistent area that drives Type A individuals to the brink of frustration and despair is when others fail to appreciate the need to do every job at the highest level and to seek excellence as the only goal. When educators insist every task a student approaches must be done with standards of excellence in mind, then excellence becomes a consistent behavior. At the same time, it should be made clear excellence is not always an innate behavior – it must be taught through example and through teaching moments. It is not taught by throwing pots and pans. - Eliminate Us VS. Them

For too long we have accepted the reality there is always an environment of friction between the front and back of the house. Educators have an opportunity to break this belief and focus on unity. The success of a restaurant depends on these areas working toward the same goal. As much as we can, a curriculum should require students to walk in both sets of shoes. - Emphasis on team

The concept of a team goes beyond teamwork. Anyone can set aside discontent and even dislike to work with others in the moment, but this does not create a true sense of team. If we spent more time, in all classes, focusing on working together, learning each other’s strengths and weaknesses, figuring out how to depend on each other, compensate, and support each other, then this will become a pattern and a method of operation graduates will rely on. When chefs fail to see the value of a team, failure to listen to others and appreciate what they have to offer, and fail to create an environment of mutual support, then the level of success a restaurant seeks may never materialize. - Walk in the other person’s shoes

Those of us with a few years of experience under our belts were trained to understand everything in a restaurant is everyone’s responsibility, no job is beneath us, and all jobs are important. The classroom is the perfect place to establish these behavior patterns. Every student needs to learn to walk in the other person’s shoes whether it is washing dishes, mopping floors, busing tables, serving guests, or working the line. They will never appreciate the other person until they themselves experience what it is like to do the other’s job. - Understand the consequences

It is our responsibility to seriously talk to students about harassment, hostile work environments, and what is acceptable behavior today. Angry, hostile chefs put themselves, their coworkers, and the restaurants where they work in jeopardy. Watching and coaching behaviors in the classroom is an essential part of education. - Teach balance

At some point in higher education, we lost sight of the importance of physical, emotional and mental exercise on performance. When a chef is accustomed to a life of balance then he or she will always seek to find ways of maintaining that regimen. Shouldn’t we encourage this in our role as educators? Walk instead of ride, find the time to read for fun as a form of escape and relaxation, sign up for a yoga class, swim, ski, cycle – whatever makes you able to step out of your current role and relax. - Set the example

Our students will always emulate the patterns of behavior exhibited by instructors. We all must be the example for others, the benchmark of professionalism, the strongest advocates for solid leadership, and the shining light of team mentality. - Create mentor lifelines

The most effective teachers understand their connection to students does not end when they walk across the stage to receive a diploma. If you are their benchmark, their mentor, their example of professionalism, then you should maintain a lifeline with them throughout their career. - Focus on problem-solving techniques

As a chef, every employee, every operator or owner, and every guest looks to you as the person who can make things right. The ability to anticipate and prepare for curve balls and the skills to solve problems is quite likely the single most important skill that separates great cooks from great chefs. We should find ways to demonstrate how to solve problems in the classroom while we have a chance. Build scenarios that force students to think, create a need for students to collaborate with others in the process of finding solutions, and create failure opportunities as teaching moments which can be discussed and dissected as part of your educational approach. With problem-solving skills comes confidence, and with confidence comes success. - Measure social intelligence

Karl Albrecht determined, “Social Intelligence is the ability to get along well with others, and to get them to cooperate with you. ... A continued pattern of toxic behavior indicates a low level of social intelligence - the inability to connect with people and influence them effectively.” It is the application of a nurturing, but firm style of interaction with others that is at the core of solid leadership. Without this, many chefs will be responsible for creating a toxic environment contrary to effective management.

PLAN BETTER – TRAIN HARDER

Paul Sorgule, MS, AAC, president of Harvest America Ventures, a mobile restaurant incubator based in Saranac Lake, N.Y., is the former vice president of New England Culinary Institute and a former dean at Paul Smith’s College. Contact him at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..