Research Article: Industry Partnerships in the Culinary Arts Classroom Point Toward a Greater Problem

06 January 2025A practical and research-based analysis of culinary education’s challenging partnership with the foodservice industry.

By Christopher Bates, MEd, CCC, CCE, NPE

Feedback & comments: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

During the summer of 2024, I attended one of those interminable Career and Technical Education conferences. You know the type: a well-meaning sponsor funds a gathering. The main speaker and specialty forums are designed around a pet theory some friend-of-education thinks will be helpful, but rarely is. It was exhausting.

There was a bright spot, however.

At a breakout session, the moderator asked a room of culinary arts educators to make an honest appraisal of our working relationships with industry partners. Blank looks from those assembled let me know that this was an unfamiliar topic for at least a few people. We spent an hour talking about how beneficial school/work partnerships could be and how important professionals from the F&B world were to our students’ success. For most of this, I nodded along as my experience, research and interviews with successful culinary programs supported their claims.

After the rah, rah, rah portion of the presentation was over, our moderator passed out a pile of brightly colored index cards and asked us to score the health of our industry relationships on a scale of 1-10, basing our score on what we had learned. I wrote “5,” flipped the card over, and perked up, curious to see how my fellow teachers would rate themselves. I was interested to see how they would justify their reckoning.

I had given myself the lowest score in the room.

I am not a pessimist. Few who have heard me wax poetically about my award-winning culinary program or my students’ successes would mistake me as a “glass-half-full” kind of chef. However, I am a realist. And on the topic of partnerships, we desperately need a tall mug-o-realism.

This essay is the first of a multi-part series. I intend to share the ofttimes uncomfortable research on where we are today in terms of industry/kitchen classroom partnerships. Future essays will focus on what research indicates needs to change and will be, I’m certain, rosier.

Please don’t be put off by the critical self-analysis I’m leading. Things will look brighter on the other side. But for now, we must take off our rose-colored glasses and make a sober assessment of how things really are.

The canary stopped singing a while ago (and nobody noticed)

A decade ago, after transitioning from restaurant work to high school education, I reached out to my contacts from the industry to get them involved with a culinary arts class I inherited from a previous teacher. No one returned my calls. I shrugged and kept working, transforming a high school teaching kitchen with 185 students into a greatly expanded Magnet Program with over 400. As the years went by, the frustration of trying to entice industry professionals to become actively involved didn’t end. These chefs and restaurant owners (people I knew) were unwilling to help advance the preparation of their future employees.

Because I’m quite the nerd, I took grad school courses at night a few years into my new position. I was intent on learning all I could to build a remarkable culinary program. As part of that work, I researched school/work partnerships as a major focus of study. In the process, my understanding of the underlying issues was clarified, challenges highlighted, and problems with the current environment laid bare. If industry/school partnerships are the canary in the coalmine - as I now believe - ours stopped singing a while ago and nobody noticed.

I remain an optimistic fellow despite all I have learned. I spend untold hours working to build a solid, empowered and engaged Advisory Board for my culinary arts program. I contact at least one new potential industry partner each month. I no longer limit myself to “fancy” outlets or even traditional restaurants. I invest in professional relationships and giveaway precious classroom time so possible partners can engage with my students. The entire process is a game of inches, not yards. I alternate between frustration, fantastic hope and a persistent sense that something needs to change.

Culinary students on a field trip to Domino’s Pizza, 4 April 2023

And here’s where change starts: culinary arts educators and program leaders need to get a more accurate grasp on the problem.

Let’s start with a fact (one that scholars have researched, had peer-reviewed, and published): effective school/work partnerships spell the difference between lackluster outcomes and powerful opportunities for students. We even know how to measure successful school/work relationships with a fair degree of accuracy. Victor Hernandez-Gantes and Dana M. Griggs, two of the leading voices on industry/school partnerships, boil down the issue to five quantifiable components. According to these scholars, effective industry/education partnerships are characterized as being:

- a close-knit network

- engaged in purposeful planning

- shared values and common goals

- open and regular communication

- all members committed to helping students become career ready

(Griggs, 2015, Hernandez-Gantes et al., 2018)

Culinary arts educators and specific F&B industry leaders are a disparate group. They are rarely clear on what they want, infrequently plan with the end in mind, almost never clarify expectations or set goals for their partnership, and frequently demonstrate a noncommittal relationship to one another and the programs they support. The relationship is more akin to a 14-year-old’s three-week love interest than a long-term partnership driving change.

Why is there so much mileage between what we SHOULD do and what we are ACTUALLY doing? I have boiled it down to three big misconceptions:

First industry misconception: The purpose of work/school partnerships is for businesses to gain entry-level employees.

Just before COVID-19 turned everything upside down, I was speaking on building industry partnerships at a gathering of hospitality and lodging leaders in my home city of Orlando. My talk led to a wonderful conversation with the vice president of a well-known and respected hotel chain. While we chatted, I was somehow able to maintain a serious, professional demeanor (while on the inside I had transformed into a giggly fanboy, thrilled at the chance of partnering with such a powerful company).

Before walking away, this executive texted a subordinate to set up what she assured was the first of many school visits. Imagine my disappointment when the representative of the company treated the occasion as a recruitment opportunity, using the time I had allotted to inspire or educate as a timeshare-sales-style pitch, one where they attempted to talk/bully/cajole my students into applying for an uninspiring hourly position at one of their locations. When no one applied, I never heard from that hotel chain again.

Unfortunately, that experience is far from uncommon. Many potential industry partners see the relationship between their workplace and the culinary arts classroom as little more than an arena to find unskilled labor. They see a fishing hole for low-paid, hourly employees. Even when they are willing to hire employees for a position more challenging than entry level cook 1 with no experience required, they aren’t satisfied with the employees we send them. We’ll return to this topic, but for now suffice it to say our students are rarely kitchen ready.

I’ve asked industry partners about this. On occasion, they have been bluntly, brutally honest, “I donated $3,000 for a handwashing sink. I fired one of your kids for always coming to work late and another for constantly messing up dishes. Since that time, none of your students have even applied to work at my restaurant. That $3,000 was wasted money.”

Second industry misconception: Companies want to give talks, host field trips and visit campuses and think that is what educators want. (In reality, educators need supplies, money and equipment.)

This issue isn’t so much a misconception as it is a two-way miscommunication.

Industry leaders tend to see investing time and resources in ANY culinary arts program as a very low Return on Investment. An executive chef may love the idea of supporting education or the owner of a small chain of steakhouses may have a genuine desire to help, but they tend to see their help in a limited light. They see things they can do that costs no money.

This is where we notice a singular difference between culinary arts programs and other types of career and technical education classrooms.

Compare a typical culinary arts program with a variety of other CTE classrooms. Car repair programs don’t have trouble getting donations of entire cars or tools or large equipment pieces for their students. I have an acquaintance who runs a high school automotive repair magnet program in South Florida. He was shocked when I told him of how I had unsuccessfully begged donors for an oven that costs 1/10th the price of just one of his hydraulic lifts.

Walt Disney World chefs and F&B executives pose with Wekiva Culinary’s

two-time national NASA HUNCH Culinary Challenge Finalists.

The same dissimilarity is true between culinary arts students and programs where students are preparing for careers in healthcare and human services, construction, and (at least in Florida) anything related to agricultural sciences. Businesses and industry associations within these fields see nothing strange about donating pricey equipment, giving core supplies, and even paying for costly infrastructure.

What’s going on? While some disparity will probably always remain a mystery, we can make educated guesses.

Due to the restaurant industry’s challenging nature, many who genuinely want to help students don’t see that help as a beneficial, long-term financial investment. Why would they? Their donation may never provide a direct, quantifiable benefit. Many managers and location supervisors don’t see themselves remaining in their current position for the next five years. Why would they want to invest precious marketing dollars in a culinary arts program where the payoff won’t be seen while they are still working there?

Sometimes, it’s not a lack of interest in investing or fear of spending company resources but it still comes down to employee turnover.

Here’s an example: an amazing executive chef and culinary director of a four-diamond, three-star resort in Orlando was charmed by my students at a community event and had finally become prepared to lend the full weight of his position to helping us grow. It took three years for me to officially win his support - three years.

We made plans to meet over the summer and nail down our objectives and schedule how everything would work. We were going to talk about classroom visits, a funded-field trip to his location, and a joint fundraising project to FINALLY install a much-needed Doyon rotating oven.

Suddenly, he stopped returning emails and weeks went by. I finally called his secretary, intent on discovering why I was so badly ghosted. She cheerfully told me she was new to the office as were most of the culinary staff. My chef friend had moved to NYC and was working for an entirely different high-end location. She apologized that his email address hadn’t been disabled and offered to schedule a meeting with one of the new guy’s assistants in a couple of months. She asked as an afterthought, “And what’s this all about?”

This has happened to me several times now. Getting powerful folks on our side takes time and then they transition to another location or company or retire. Or maybe company leadership changed and suddenly supporting local education is no longer a priority, or maybe another maybe.

Select Wekiva culinary seniors, posing in our kitchen with the senior leadership team of

Universal Studios’ Food and Beverage Division, including Senior Vice President Mandy Bond

and VP and Corporate Executive Chef Stephen Jayson; 11 October 2021.

Restaurant owners are fully aware of their businesses’ precarious nature and they aren’t interested in making a community investment with little “bang for their buck.” It is better to buy new jerseys for a little league team or new tents for a scouting troupe. The picture of restaurant employees smiling beside little kids in their uniforms might get into the newspaper and would at least drive community acknowledgment and potential market share.

What about big companies like Vulcan, Vollrath, BUNN, Robot Coupe, Doyon, and others? These manufacturers - creators of the marvelous equipment we need to install in classroom kitchens - see schools as customers, not as training grounds where it would be wise to donate their product. Some advertise they support education but access to those supports is hidden and may exist as an ideal more than a reality.

Some, like RATIONAL, have very good education pricing. But for your average, underfunded-public high school, half of $58,000 is still a number so far out of reach it is almost comical. I CRAVE an iVario Pro Tilt Kettle. It would be a game changer in many, many ways. But I don’t have access to $20,000 and we don’t have any donors willing to help with something holding a price tag that heavy.

| Until this point, this essay has focused on the challenges affecting secondary and post-secondary publicly funded culinary arts programs. The article did not apply to private, for-profit culinary schools. The rest of this work? It impacts us all. |

Third educator misconception: We’re doing a great job. (They are not buying what we are selling.)

This point is undeniably the most important and the one MANY of my culinary educator friends and colleagues will take issue with.

Few outside the culinary education bubble believe what we are providing is necessary or even all that valuable.

I disagree with them and have solid arguments for our value. My counterpoints don’t diminish the truth: the public isn’t buying what we’re selling.

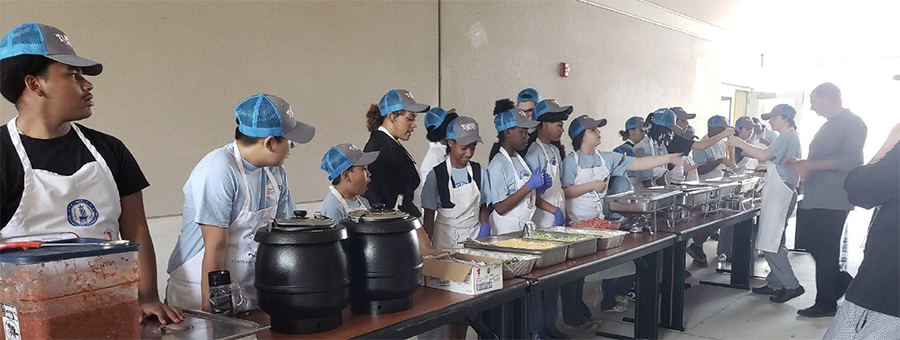

Wekiva Culinary students cook alongside third and fourth graders at a local elementary school,

cooking and serving “Tacos-for-Teachers” to 180 faculty and staff; 27 March 2024.

Culinary arts teachers need to become comfortable with this very uncomfortable reality: there is a pervasive lack of faith in culinary arts programs of ANY stripe producing cooks ready for the commercial kitchen on day one. To put it another way: the skills, values and work habits our partners want new employees to have are not the skills, values and work habits we are teaching.

This is a fundamental fact, underscored by a significant quantity of research. Feel free to check the references at the bottom of this essay. What you read will probably upset you if you did not already know it.

Is the public’s lack of confidence merely a problem of perception? Do we need to invest more of our time and limited resources in a generalized marketing campaign to improve the perceived value of technical education? The research says, “Yes. A bit. But mostly, no.”

There are many innovative programs and instructors, talented chef educators struggling to address the disparity between what we teach and what industry leaders and community partners want. I count myself as one of these. I regularly talk with hiring managers at restaurants, resorts, and two of the world’s biggest theme parks. I ask them what values, skills and work habits they want us to focus on, what will give our graduates a leg-up in their kitchens, what traits will make them decidedly hirable? This is one of the primary indicators of a strong school/ work partnership: investor input into curriculum and student outcomes. Their suggestions have radically changed the way we do things and perhaps in a later article, I’ll share some of the fundamental, structural evolutions we made in my program.

And I am not alone! Many chef educators are pursuing a similar path, working diligently to train their students with the values, skills and work habits our industry friends want.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of teachers and entire culinary schools are training students as they did 50, 75, or 100 years ago! These schools are marked with a heavy focus on specific theory and technique, with little emphasis on the grinding challenge of the line and creating generative and transferable skills like communication and planning, sense of urgency or food cost awareness.

This is not my opinion. It is the damning judgment of our critics. It is the opinion of human resource workers who report having to terminate or reassign our graduates. It is the opinion of the hiring class, where what should be a simple onboarding process turns into a deep and basic retraining. Worse still, it is the opinion of many of our graduates, who report not feeling prepared after getting a job, of feeling misled and fed promises which did not bear fruit.

As a result, we continue to see the same large percentage of graduates leaving the workplace within their first three years of restaurant employment. Some reports claim the number to be as high as 50%.

And how is our reputation faring among the station cooks and sous chefs, the folks who work side-by-side with the students who remain? We hear the same tired line, “I’d rather bring on a Denny’s line cook than a culinary grad.”

As if all this wasn’t enough, we are witnessing the steadily diminishing reputation and enrollment numbers of one culinary arts school after another. Why are more and more students opting out of our programs? Enrollment numbers are dropping at least in part because there is a snowball-rolling-down-the-mountain movement, a viral TikTok/Instagram/Snapchat message circling the 20-something crowd proclaiming culinary arts education is worthless.

Adding yet a final crushing weight to the avalanche, employers have NEVER required applicants to hold the education or certifications we provide. Similar challenges can be laid at the feet of the American Culinary Federation, an organization I remain a proud member. We offer certifications and degrees, but the workplace doesn’t REQUIRE them. And why would employers require a culinary school diploma from one of their workers? Why force an applicant to show our credentials to take a position as a sous chef or ACF certification to work as a chef de partie? We’re not training our students with the values, skills and work habits those workplaces need. Our grads don’t walk into their kitchen job-ready and for some reason, we have simply accepted it. Our students have NEVER been prepared for work on day one.

So, as John Oliver might say, “What can we do?”

I believe in culinary education, deeply and passionately. I can make a case for what I teach that I believe is compelling and rational. However, the canary has stopped singing. We NEED to make aggressive and deep changes to our institutional model to remain relevant. I believe we must make these changes to continue to exist at all.

There is a mountain to move and our first task is simply to acknowledge the mountain is there. Once that incredibly basic hurdle is crossed, we can begin to rethink on a fundamental level what we are attempting to accomplish and what are the first steps in that direction.

Oddly enough, the very thing that points to our problem - effective industry partnerships - is the key to becoming relevant again.

References and Source Materials

Baradaran, Robert. California Culinary School Graduates’ Perspectives on Their Education Programs. Diss. Walden University, 2024.

Bauer, Kristina N., Samuel T. McAbee, and Michelle L. Jackson. "From classroom to kitchen: Predictors of training performance and transfer of culinary skills." Learning and Individual Differences 105 (2023): 102315.

Brough, David E. The relationship of the required knowledge and competencies of the American Culinary Federation Foundation Accrediting Commission (ACFFAC) for post-secondary culinary arts programs to the perceived needs of the workplace. Diss. State University of New York at Albany, 2008.

Edens, David. "Predictors of culinary students' satisfaction with learning." Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education 23.3 (2011): 5-15.

Gersh, Irish. Culinary industry practitioners and educators' perceptions of core competencies for a four-year bachelor's degree in the culinary arts. Seton Hall University, 2011.

Gonzalez, Jonathan J. From chef to educator: An exploration of the experiences of new culinary arts instructors. Northcentral University, 2016.

Griggs, Dana M. "A Case Study Of A School-Industry Partnership." Creating School Partnerships that Work: A Guide for Practice and Research 11 (2020).

Hernandez-Gantes, Victor M., Sasha Keighobadi, and Edward C. Fletcher Jr. "Building community bonds, bridges, and linkages to promote the career readiness of high school students in the United States." Journal of Education and Work 31.2 (2018): 190-203.

Heyward, Georgia. "Schools Lead the Way but the System Must Change: Rethinking Career and Technical Education." Center on Reinventing Public Education (2019).

McGeever, Amy. “Culinary School: The Pros and Cons of Culinary Education”. Eater. 11 Jul. 2013. https://www.eater.com/2013/7/11/6408893/culinary-school-the-pros-and-cons-of-culinary-education.

Müller, Keith F., et al. "The effectiveness of culinary curricula: A case study." International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 21.2 (2009): 167-178.

Padavan, Anthony Joseph. "A Phenomenological Exploration of Career Progression Among Culinary School Graduates." (2018).

Raskin, Hanna. “Culinary schools struggle to match realities with perceptions in restaurant work.” The Post and Courier. 28 Dec. 2022. https://www.postandcourier.com/food/culinary-schools-struggle-to-match-realities-with-perceptions-i n-restaurant-work/article_261ad696-9f97-11e7-8ca1-17668f912867.html.

Riggs, Michael W., and Aaron W. Hughey. "Competing values in the culinary arts and hospitality industry: Leadership roles and managerial competencies." Industry and Higher Education 25.2 (2011): 109-118.

Rinsky, Glenn. Test kitchen: An examination of a community college's assessment for graduating culinary arts students. Diss. Capella University, 2012.

Sorgule, Paul. “Why Culinary Programs Fail.” Harvest America Blog. 15 Mar 2021. https://harvestamericacues.com/2021/03/15/why-culinary-programs-fail/

Test, Earle M. Considering the Value of Postsecondary Culinary Education. Diss. Northeastern University, 2022.

*******************************************************************

Chef Christpher Bates earned the Orange County Public Schools Teacher of the Year in 2020, was selected as ProStart Florida Teacher of Excellence in 2023, and received the James H Maynard National Award for Classroom Innovation in 2023.