Throw Out the Recipes, Part II

07 October 2014

This second in a two-part series on teaching culinary arts through ratios in practical culinary labs focuses on incorporating ratios into your lesson plan.

This second in a two-part series on teaching culinary arts through ratios in practical culinary labs focuses on incorporating ratios into your lesson plan.

By John Reiss, CEC, CCE

In my previous article, I wrote about using ratios in professional culinary training. Here, I focus on the ratios themselves and how to incorporate them into your lesson plan.

Ratios in Professional Cooking

As professional chefs and culinary educators, we use ratios that might be explicit or subtle. On one hand, for example, we know that a pilaf is 2:1, vinaigrette is 3:1 and a roux is 1:1.

On the other hand, there are ratios that we apply instinctively and without much thought. We “know,” for example, the amount of water needed to prepare a stock, or the amount of salt we should add to water when preparing pasta.

Knowing ratios like these streamlines the cooking process and creates speed and efficiency—both valuable commodities in the kitchen—where time is of the essence. It’s also liberating to have ratios like these at our fingertips, because they provide a zone in which we can channel our creativity in developing techniques and methods.

Ratios in cooking include the following features:

- A fixed proportion of ingredients in relation to one another

- A baseline to codify the fundamentals of cooking

- Common culinary techniques simplified to create efficiency

- A process for easily scaling production to the quantity desired

- A code that unlocks the ability to create thousands of recipes

Types of Ratios

Ratios are calculated by weight, volume or as mixed ratios incorporating a combination of weight, volume or even count. (For example, a hollandaise ratio is 6 yolks to 1 pound of butter.)

Examples of ratios by weight include a roux or a bread dough, and by volume a simple syrup, a pilaf or a vinaigrette.As a way of speeding and simplifying the cooking process, these and other simple ratios are helpful and, particularly compared to a recipe, relatively easy to memorize.

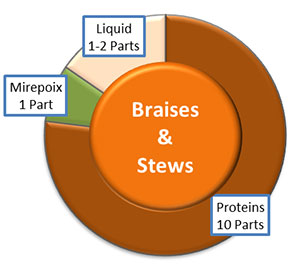

Ratios can be devised for almost any preparation, even complex ones. For example, a basic ratio for a braise uses 10 parts protein, 1 part mirepoix and 1 to 2 parts liquid as its foundation. This simple ratio can be applied to any braise or stew, whether you are preparing a pot roast, a fricassee or an African tagine. The mirepoix may morph into an Italian soffritto, or incorporate mushrooms, garlic and shallots. The liquid may include wine or beer, and the fat may be olive oil, butter or duck fat.

Even with all these variables, however, the process—and the ratio—holds true. There are ratios for soups and sauces, risotto, grains and legumes, and bread and pastry. Once you start thinking in ratios, the possibilities are endless.

Ratio Guidelines

Ratio Guidelines

Ratios require a solid foundation in culinary skills and a healthy dose of common sense. Ratios include only the major components of a preparation and don't include additional flavorings or seasonings that might alter their mix and cause yields to fluctuate based on the additives.

Ratio Challenges

I prefer ratios based on weight because weight is absolute, while volume (especially dry ingredients) is variable. For example, I use a ratio for a stock that calls for 3 parts liquid to 2 parts bones (3 pounds water to every 2 pounds of bones).

You might be able to see the potential for confusion when students have to convert 3 pounds water to a liquid measure. This is when standardized recipes and ratio-conversion examples become a relevant part of the lesson plan. So now we discuss a standard recipe using a mixed ratio of liquids based on volume (5 to 6 quarts of water) to the weight of bones (6 to 8 pounds) and mirepoix (1 pound) per gallon yield. This process dovetails ratios with recipes and shows students how the two work together.

Ratios in Reverse

Ratios can also be used to develop recipes, and recipes can be evaluated through ratio analysis to test for accuracy. This is an especially helpful teaching tool in the culinary lab. In fact, I no longer supply students with recipes. Instead, I give them a ratio and tell them to find a recipe. Then we work backward, and they create their own recipes.

Ratios: the Chef’s Code

In the film Pirates of the Caribbean, Captain Barbossa says, “The [Pirate’s] Code is more what you’d call guidelines than actual rules.” Think of ratios as the “Chef’s Code” that help guide you in the kitchen. They are one tool in your kit, and they work in proportion to the amount of common sense applied.

They are only as good as the cook executing them. Solid culinary skills, good organization, accurate measuring and the ability to balance flavors and seasoning are just as important. But ratios help students learn to cook intuitively and unchain them from the written recipe.

Throw Out the Recipes—Ratios and Culinary Education

As an instructor, I was a little apprehensive about adopting this theory of ratios to the kitchen lab. After all, I was locked into the traditional model of recipe-based instruction, having relied on it for so many years.

It took a leap of faith, but I have found that it works for me, and it can work for you. I’ve taught culinary ratios in basic to advanced kitchen labs, and I have found that once students don’t have recipes to fall back on, they take more notes, ask more questions and pay more attention to kitchen demonstrations. There is more of a dialogue and give-and-take in the lab. Ratios help students cross the bridge from the culinary lab to the professional kitchen.

John Reiss, CEC, CCE, is a chef-instructor at Milwaukee (Wis.) Area Technical College.