Throw Out the Recipes, Part I

10 September 2014

Says this educator, ratios trump recipes in helping students learn. The first of a two-part series on teaching culinary arts through ratios in practical culinary labs.

Says this educator, ratios trump recipes in helping students learn. The first of a two-part series on teaching culinary arts through ratios in practical culinary labs.

By John Reiss, CEC, CCE

Are we training students the right way or the wrong way? That’s a loaded question, and one that culinary educators can easily become quite defensive about. The knock in culinary education often comes from professional chefs who say we aren’t training students to be seasoned and productive when they graduate.

Having taught in the industry for more than 25 years, I have often pondered and debated with peers over best practices for preparing students to be job-ready when they finish their studies. I have come to the conclusion that maybe there is a better pedagogical approach, one that involves the use of culinary ratios.

We often teach students practical competencies through the aid of recipes. Why? It’s true that recipes are important to some extent in the kitchen, but most professional kitchen work relies on intuitive cooking, standardized techniques and procedures and proper mise en place, rather than recipes.

Traditional on-the-job training employs these concepts—not recipes—when training new employees. Since we don’t have the luxury of time that allows for practical repetition to take hold in an intuitive sense, maybe a better approach to teaching practical skills to our students is through the use of ratios.

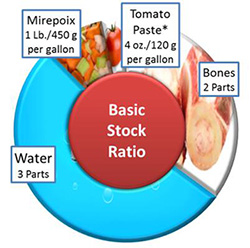

Ratios are universally recognized by chefs for creating efficiency and saving time in the hectic environment of a professional kitchen. Methods and procedures, along with experience and standardized tasks, trump recipes. A well-honed cook learns the nuances of cooking, adjusting flavors and seasonings and manipulating textures and consistencies, often applying these techniques intuitively. Many of these methods revolve around the use of ratios.

Think about the simple ones we all know—mirepoix, rice pilaf and vinaigrette. There are others that I’m sure you can rattle off without even thinking too hard.

Recipe Limitations

Recipe Limitations

Recipes have their limits in academics and professional kitchens alike. They teach students to do things one way and expect a successful outcome. They don’t teach the need to think through the process, make observations, evaluate conditions and make adjustments accordingly. When something doesn’t turn out, the standardized response is often “but I followed the recipe.”

Ratios are a better approach to culinary training because they provide students a broad foundation that can be built upon and developed, based on available ingredients, creativity and inspiration. This might be a more realistic teaching approach, because in a professional kitchen, what line cook has time for recipes?

To be fair, recipes play an important part in maintaining consistency and quality and keeping food costs in line. Recipes are useful when you know instinctively what to expect. They are especially important in baking and pastry work, house recipes and signature dishes. And yes, teaching recipes helps students understand standardized methods and acquire the ability to follow written directions.

But often recipes become a crutch. Students pay too much attention to the printed words, and don't focus on what’s happening in the pan. As chefs and instructors, we have years of experience and know instinctively when something looks right by appearance, aroma, texture, touch, taste and mouthfeel.

Students with little experience and no expectations are hesitant and often puzzled about the process. They are often afraid to take risks, and they lack confidence to make adjustments. Coupled with novice challenges such as their lack of speed, sense of urgency and ability to multitask, and we might be setting them up for failure in the industry.

Ratios as a Bridge

Ratios are a bridge from the culinary lab to the professional kitchen. They are a valuable communication tool for teaching because they require students to be actively engaged in the learning process. They open up a dialogue between instructor and student to review techniques, ingredient characteristics, variables in the cooking process, variations and substitutions and tips and nuances of a preparation. A ratio opens student’s eyes to creative possibilities and helps them evaluate the cooking process using skills of observation: sight, sound, texture, color, flavor and consistency.

Throwing out recipes and instead teaching ratios requires a two-way social interaction and not a written recipe to convey the lessons, goals and objectives of a particular competency.

In fact, as innovative as it might seem at first glance, teaching ratios might actually be closer to a traditional apprentice-mentor model of training. If you teach students a recipe, they learn one recipe. If you teach them ratios, they learn to cook intuitively across a wide variety of preparations.

For this reason, teaching ratios has become my guideline in the culinary lab.

Next month in “The Gold Medal Classroom”: incorporating ratios in your lesson plan.

John Reiss, CEC, CCE, is a chef-instructor at Milwaukee (Wis.) Area Technical College.